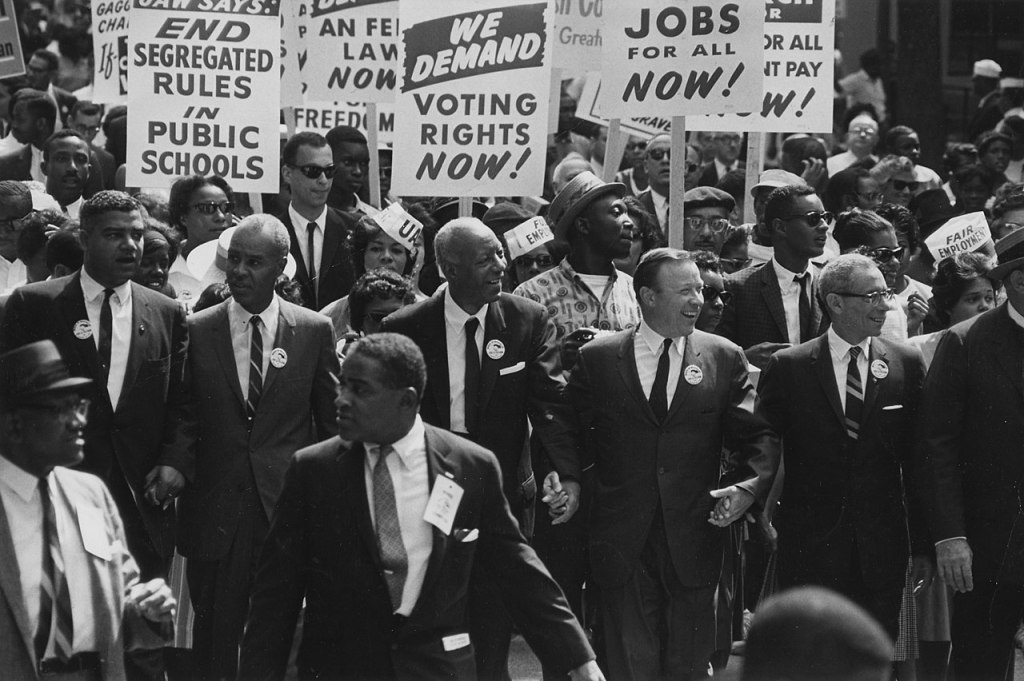

Night after night, during the long, hot summers of the early postwar decades, television screens across the nation cast glowing black and white images of the evening news into the family rooms of America. Reflected in the eyes of viewers were scenes of Civil Rights marchers moving along in solemn files, usually taunted and jeered at by crowds who flung ugly oaths at them. Occasionally, a rapid movement would catch the eye as a hostile bystander, intending harm, would hurl an object at them. Those not fortunate enough to dodge the missile suffered the attack, but the marchers’ spirits never seemed to waver under the heat of the assault. Police and authorities often stood back letting the mob’s aggressions play out, or took actions of their own to interdict the marchers by deploying water cannons, gas, and snarling dogs. Still, as these dramas played out, the marchers continued on, moving inexorably through the towns, cities, and segregationist citadels of the American South where the long-held cultural consensus had so long denied them the liberties they sought. Place names like Birmingham, Washington, Little Rock, Atlanta, Montgomery, and Selma served as markers along the trail they journeyed, and so also became etched as scars into the national psyche.[1]

As they marched, they breathed words about freedom, justice, and the familiarity of suffering, and their songs rose high above them like prayers caught on the wind. The lyrics followed from Gospel verses that almost every man, woman, and child among them knew by heart. They were words that had echoed for centuries from church pulpits, lifting to the rafters, and settling upon the congregations. They were lyrics rooted in faith and hope, and anchored in Holy Scripture. It was the language of the American Civil Rights movement. By the 1950s, this music of faith had become the voice of that crusade. It made sense that it flowed from that foundation, the one place where enslaved and marginalized people could find refuge during their years of oppression. Songs such as “We Shall Not Be Moved” (Psalm 62:6) spoke of resolve, and “We Shall Overcome” (John 16:33) encouraged perseverance in the face of adversity. They emerged from scriptural passages, lifting souls up from despair and offering them hope, a hope that translated into the struggle for civil rights.

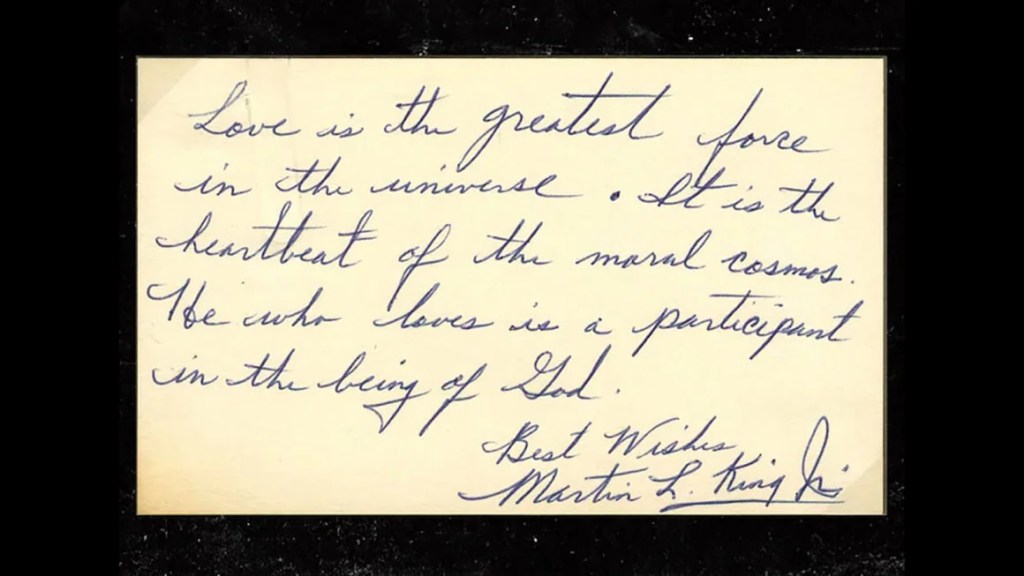

The leadership of the movement too came from that same place, through the clergy. Among them were the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Ministers Fred Shuttlesworth, Ralph Abernathy, C.T. Vivian, and others who spoke of the redemptive powers of forgiveness (Romans 5:10), love (1 Peter 4:8), and suffering (Romans 8:18). Addressing packed churches these men drew their inspiration and energy from the Bible, using it to encourage the formation of a grassroots movement that would carry their cause forward, but they also eschewed violence in its name.[2] As Scripture cautions against joining the wicked in drinking the “wine of violence” (Proverbs 4:17) and against its incessant pervasiveness in all actions (Isaiah 59:1-6), King preached that violence “is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible.”[3] He also offered a foil against the violence and hatred directed at them by writing, “Love is the greatest force in the universe. It is the heartbeat of the moral cosmos. He who loves is a participant in the being of God.”[4] Those ideas have been his legacy, and were the heart and soul of the early struggle for civil rights in the United States during the first postwar decades.

Those who teach and study history often fail to underscore the spiritual foundations of the incipient Civil Rights movement. The light of political and cultural turmoil of that day blinds many scholars to the reality of Scripture’s centrality to the cause. So, it is important to remember that it is in God’s word that we can always find encouragement to treat one another with justice and fairness. For Paul reminds us, as he had the Galatians, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” (Galatians 3:28)

[1] Perhaps the best remembered march and gathering was at the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963. It was the site of King’s famous “I Had a Dream” speech.

[2] For more about how the Bible influenced and shaped the tenets of the early Civil Rights Movement see Richard Lischer, “In the Mirror of the Bible,” Chapter 8, The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word that Moved America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[3] MLK’s Nobel Prize Lecture, “The Quest for Peace and Justice,” 11 December 1964, accessed 19 December 2024, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/lecture/.

[4] Alicia Lee, “Martin Luther King Jr. Explains the Meaning of Love in Rare Handwritten Note,” CNN, 9 February 2020, accessed 19 December 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/09/us/martin-luther-king-jr-handwritten-note-for-sale-trnd/index.html.