Tracing the rails from Baltimore to Gettysburg, Lincoln’s train rolled past station after station as it followed the afternoon sun to the west. On the platforms rested lines of neatly stacked empty coffins. Reflecting in the windows of the president’s car, they would have appeared to his gaze as grim reminders of the somber task that lay ahead. The purpose of the pine, poplar, and oak boxes was to collect the battlefield remains of loved ones destined to return home or to their eternal rest under the broad Pennsylvania skies.[1] Some newspaper accounts recorded that their numbers rivaled those of the crowds of riders on the B&O rail line who jostled one another to pay a premium for a seat to carry them to the dedication of the new national cemetery at Gettysburg.[2] There, on the next day, 19 November 1863, Lincoln was to address the gathered masses and media at a grand consecration ceremony. Accounts don’t reflect if the people arrived before the coffins, or if the coffins arrived first, but both would serve as witnesses to the war’s devastation at that place.[3]

Along the way, the president’s journey broke several times for engine changes and to make necessary mechanical adjustments. But it was at Hanover Junction that the Reverend M. J. Alleman of St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church coaxed Mr. Lincoln from the train to offer a few words to the gathered crowd of cheering locals. These words drew the president forth: “Father Abraham, come out, your children want to hear you.”[4] The biblical imagery (Genesis 17:5) was intentional and not lost in the moment, as Lincoln was the patriarch of his people, and resolute in his faith. The president obliged the reverend, and after exchanging a few brief pleasantries that seemed to please the upturned faces of the smiling crowd, was on his way again.

Several years earlier in June 1858, in his acceptance address for the Illinois Republican Party Senate nomination, Lincoln underscored his stance on the state of slavery in the nation with the words found in Mark 3:24-25, “If a house is divided against itself, that house will not be able to stand.” From the time of that pronouncement through the remainder of his presidency, he relied on scripture to provide structure and meaning to his thoughts. As he had once noted, the Bible was the “best gift God has given to man.”[5] In truth, it was a book that was highly revered by most of the nation at the time. Subsequently, Lincoln had issued Proclamation 85 on 12 August 1861 and Proclamation 97 on 30 March 1863, both calling for national days of fasting, prayer and humiliation. They were meant to be times of reflection and repentance and an admonition that the “awful calamity of civil war which now desolates the land may be but a punishment inflicted on us for our presumptuous sins.”[6] Regardless of the nation’s earnest petitions, however, between that March and his arrival at Gettysburg in November, an additional 15,000 blue and grey lives had been lost in the bloody contest between the North and South.[7] The weight of that knowledge must have pressed heavily on Lincoln.

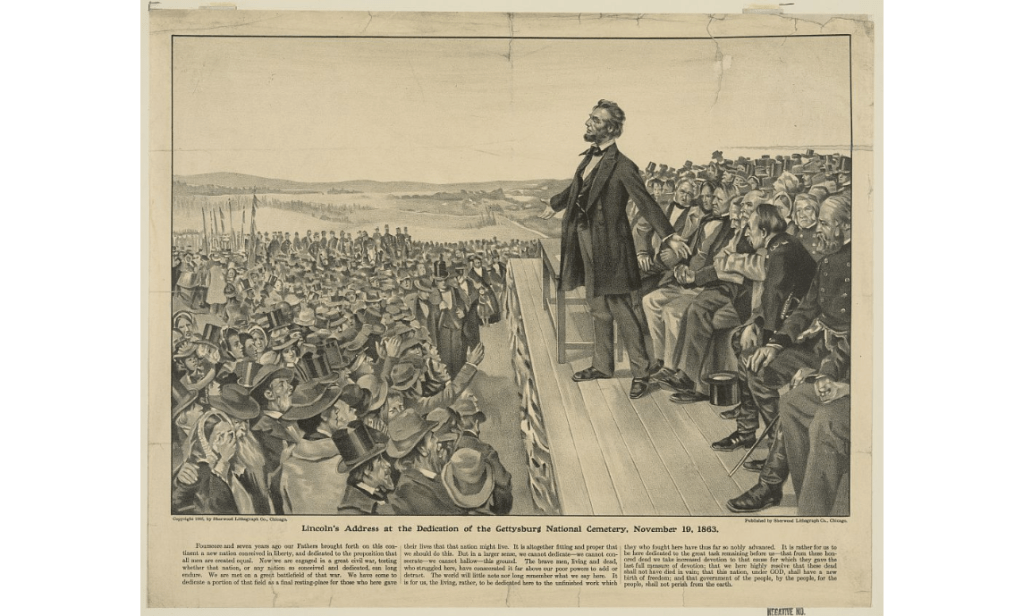

Arriving at Gettysburg in the late afternoon, Lincoln traveled by carriage from the station to the home of local attorney David Wills, who hosted him for the evening.[8] That night, the president suffered the burden of his thoughts, concerned for the state of the nation and distracted by the health of his dear son Taddie, who lay bedridden back in Washington still in recovery from a case of typhoid fever.[9] It was against this backdrop that some scholars suggest Lincoln scripted his comments for the next day.[10] The president awoke on the 19th to a day that was clear and bright, and at 52 degrees was quite mild for the season. Later that morning, at ten o’clock, with his long frock coat flapping in the breeze, Lincoln, together with his aides, followed in procession behind the ceremony’s Chief Marshal and his officers. They were in the lead of hundreds of participants, including representatives of several federal departments, various members of Congress, bearers with the flags of the states, committees of different religious bodies, representatives of the Soldiers’ Relief Association, the Knights Templar, and the Odd Fellows, a local Masonic fraternity, assorted fire companies, scores of citizens from several northern states, and members of the press corps.[11] Witnessing it all were the families of the participants, the citizens of Gettysburg, and hundreds of wounded Union soldiers still in recovery. Sprinkled in among the last group were also handfuls of wounded Confederate prisoners, left behind when their army withdrew to the south after the battle. From the town square, the procession moved south along Baltimore Street, turning onto the Emmittsburg Road, then onto the Taneytown Road, eventually arriving at the designated site on Cemetery Hill just south of the town, a total distance of approximately three quarters of a mile.

The dedication ceremony began with a musical prelude of “Old Hundredth” played by the U.S. Marine Band.[12] Following this was a brief invocation by the Reverend T.H. Stockton, who appealed to Heaven to bring comfort to the bereaved families as well as to the sick and wounded soldiers.[13] A second musical interlude consisting of the hymn “Consecration Chant” sung by the Baltimore Glee Club followed. The president, however, would not be the first to speak after the reverend’s supplication, nor did the program list him as the keynote speaker. Edward Everett held that honor. Known nationally for his oratory skills and eloquence, Everett spoke for over two hours recounting the battle at Gettysburg, the glorious Union victory, and the sacrifices made by the soldiers.[14] After a brief pause to allow for applause and murmurings of approval, another brief musical interlude followed. At its conclusion, Lincoln rose to speak. In comparison with that of his predecessor, the president’s presentation may have initially appeared too perfunctory. Still, in only 272 words, Lincoln was able to capture the mood of the nation and the spirit of the time.[15] But, as history notes, it was only an uneasy silence from the nonplussed audience that hung in the air after his final words. Eventually, a hesitant but polite applause began to ripple through the crowd as the president retired from the podium. Immediately afterward, a choir performed “Dirge,” a short composition by Alfred Delaney.

Perhaps Lincoln’s delivery was less than the audience expected, particularly after enduring the assault of Everett’s cascading oration. Or perhaps Lincoln’s words carried the weight of deeper meaning that took time to register in the hearts and minds of those who heard them. Nevertheless, Everett kindly wrote Lincoln days afterward, saying, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”[16] To this, the president graciously replied, “I am pleased to know that, in your judgment, the little I did say was not entirely a failure.”[17]

The text of Lincoln’s address is noteworthy and remains etched in history. Since the day of its proclamation, it has continued to gain in significance as an emblem of Lincoln’s legacy of compassionate leadership and his commitment to maintaining a spiritual foundation for the wounded nation. Woven throughout its text are meaningful allusions to scripture. Lincoln made this apparent from the opening phrase, “Four score and seven years ago…,” which follows a descriptive style that echoes the words of both Psalm 90 and the Book of Esther 1:4. Throughout his narrative he offered hope for the rebirth of the nation from the ashes of a destructive war to a reunification of the broken halves and from the sacrifices of the “honored dead” to the task of the living who must dedicate themselves to the “unfinished work” of healing. He continued on to charge that the dead “shall not have died in vain” and their ultimate sacrifice, like that of the Messiah, will bring a “new birth of freedom,” an eternally Christian-centered message. All of this, as he noted simply, is to be “under God.” Scholars recognize these connections and remind us of the reliance of Lincoln and the country on His eternal mercy as the dark clouds of war hung low over the bleeding nation. In this, we recognize Lincoln’s humility (Proverbs 18:12, 15:33, 22:4) and his contrite heart (Psalm 51:17) that encourages us also in our darkest hours to seek out and rely on God’s grace and mercy.

[1] The intention was to inter only the bodies of the fallen Union troops at the new cemetery. Confederate dead lay in shallow graves where they had fallen in woods or fields scattered across the Gettysburg landscape.

[2] This was the same rail line that would carry the president home to Illinois after his death.

[3] The battle resulted in a combined number of over 7,000 deaths from both armies. See American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/gettysburg, accessed 5 March 2025.

[4] William Anthony’s 1945 book, Anthony’s History of the Battle of Hanover, 50. See same at https://npshistory.com/series/symposia/gettysburg_seminars/15/essay3.pdf accessed 10 March 2025.

[5] A.E. Elmore. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: Echoes of the Bible and Book of Common Prayer. Carbondale: Southern University Press, 2009, 11.

[6] The date he set was 30 April 1863. Proclamation 97, “Appointing a Day of National Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer,” https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-97-appointing-day-national-humiliation-fasting-and-prayer accessed 7 March 2025.

[7] This includes the totals for the battles at Chancellorsville and Chickamauga. See American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/chancellorsville and https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/chickamauga, accessed 5 March 2025.

[8] David Wills was a prominent local attorney who sat on the boards of several colleges and was instrumental in directing the recovery of the town in the aftermath of the battle, and in the establishment of the national cemetery.

[9] Taddie was Thomas Lincoln, the fourth and youngest of the family’s sons. At the time of the Gettysburg Address he was ten years old. He died at the age of eighteen.

[10] Others adhere to the popular story that Lincoln penned his famed address on the back of an envelope while aboard the train enroute to Gettysburg. Another tale adds that he borrowed a pencil from a young train engineer, Andrew Carnegie the future railroad magnate. That remains unsubstantiated. See Peatman, 83.

[11] The official program for the day provides little detail other than listing these organizations in general.

[12] “All People on Earth Do Dwell,” colloquially known as ‘Old Hundredth’ was one of the most popular hymn tunes of that time. It originated from Psalm 134 in the Second Edition of the Genevan Psalter. The current name derives from Psalm 100, thus the title. John Phillip Souza’s father was a member of the band, and as a nine-year old he was in attendance for the performance.

[13] Stockton served as chaplain in the House of Representatives in 1859 and 1861, then as Chaplain of the U.S. Senate in 1862.

[14] Everett had served as the Governor of Massachusetts, US Senator from Massachusetts, US Minister to the United Kingdom, and the 16th President of Harvard University. He earned the nickname, “Ever-at-it,” a play on his name, for his typically long-winded oratories. In 1860, Everett had run against Lincoln on the Constitutional Union Party ticket together with Bell.

[15] For the full text of the speech see, “Gettysburg Address Delivered at Gettysburg, PA,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.24404500/?st=text , accessed 11 April 2025.

[16] Abraham Lincoln online, “Speeches and Writings,” https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/index.html , accessed 4 April 2025.

[17] Ibid.

Leave a comment