Nature, and Nature’s Laws lay hid in Night.

God said, Let Newton be! All was Light.

Alexander Pope, Epitaph for Sir Isaac Newton (1735)[1]

In a most profound way, Isaac Newton’s birth foreshadowed his life. It occurred on what an English novelist might describe as a perfect holly and ivy Christmas Day, in 1642, and because it was in Lincolnshire, England, the parish recorded it as a Julian date. Had it been a mere day’s voyage by ship to the east, on the Continent, it would have been on January 4th 1643, since the remainder of Europe had already adopted the changes made to the calendar proposed by Pope Gregory XIII.[2] Thus, one of the greatest minds of the Scientific Revolution measured his days according to two different rubrics of time. This was little different than the path of scientific discovery his life would travel as it coursed between secular and spiritual aspects. Both existed at the same time, each maintaining a seemingly different, yet parallel, character. Thus, the virtuosi of Newton’s day located themselves in one camp or the other. This they based on the issue of whether science was indeed rational and could be divorced from the hand of God, or if the finger prints of God were discernable on the universal blueprint. It was Sir Francis Bacon who in his Advancement of Learning made the case for the widely accepted notion that men should keep God and science separate by stating they would do well to “not unwisely mingle or confound these learnings together.”[3] Heeding this, the learned community generally acquiesced, including that the Royal Society of the day, which never examined a scientific theorem through the lens of theology. A metaphor that scholars often cite to illustrate the two positions is the comparison between the Book of Nature and the Book of Scripture.[4] The former is essentially religious and philosophical and describes the relationship between religion and science. The latter, is the Bible that describes God’s imperative in nature. So that in the first we can learn more about God through nature, and in the second more about nature through God. Or, as St. Paul had noted in Romans 1:20, as a chastisement to idolaters, “For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.”

Among the day’s illuminati Newton positioned himself with a foot in each camp. Celebrated for his many achievements in chemistry, astronomy, optics, and mathematics, he might have found it tempting, even rewarding, to maintain allegiance to the scientific purists, but he did not. Evidence reveals a man whose personal nature never forsook the spiritual aspect of his life that saw him join a commission to build fifty new churches in the London area, and pay from personal funds for the distribution of bibles to the poor. More to the point are his writings that clearly reveal a keen scientific mind that subscribed to a strong belief in God. Even before his great opus, Principia, Newton penned an intimate religious text in 1662 that was a confession of forty-nine sins committed before Whit Sunday of that year including “Not turning nearer to Thee for my affections. Not living according to my belief. Not loving Thee for Thyself.”[5] He was not a man who could easily divorce himself from the essence of spirituality even as he influenced scientific understanding. Though he never sought to draw attention to his theological beliefs, so as to avoid public controversy, he continued to write about them. Archives and collections contain his non-scientific works on Observations upon the Prophesies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733), several works on church history, and a number of drafts of an Irenicum.[6] Important also as evidence in this regard was Four Letters from Sir Isaac Newton to Doctor Bentley, Containing Some Arguments in Proof of a Deity, published in 1756 nearly thirty years after his death.[7] In this collection he wrote to Bentley who was then serving as Master of Trinity College, Newton’s alma mater. In these missives it is clear that he saw design in the universe as a system requiring “a cause which understood and compared together the quantities of matter in the…Sun and planets and the gravitating powers resulting from thence.”[8] To Newton it was no coincidence that planetary motion and the orbits of comets were mere happenstance.

Newton’s greatest admission of a Divine plan finally emerged in his seminal work, The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, colloquially known as his ‘Principia.’ Although the first of three editions (all in Latin) appeared in 1687, it was the 1713 version in the “General Scholium,” an appendix to the greater work, where he confessed his grand design stance.[9] Here it is, after three sections filled with his scientific findings, theorems, and propositions that Newton writes, “This most beautific [sic] system of the Sun, planets, and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being.” He continued, “This Being governs all things, not as the soul of the world, but as Lord over all; and on account of His dominion He is wont to be called Lord God…He is supreme, or most perfect…He is eternal and infinite, omnipotent and omniscient.”[10] Above all, His hand is in all and orchestrates all.

The Scientific Revolution was a period of time beginning with Copernicus and concluding with Newton when men felt drawn by the gravitational pull of the classical sciences. For some, it offered the promise of a new ego-centric landscape where Man was the emergent master discovering the key to the mysteries of the universe, and where Nature was merely a mistress who Man could eventually manipulate and seduce to reveal her secrets. But Newton would not concede to the absence of God’s manifest influence. He truly believed that his own work was an extension of his faith and this drew him closer to knowing God, and that a further study of the sciences and nature could lead mankind to a closer relationship with the Supreme Being who was the architect of the universe. As the words of Psalm 111:2 tell us, “Great are the works of the Lord, studied by all who delight in them.” To those of great intellect during Newton’s time, who stood with hubris disparaging his claims, God’s words to a reproved Job seem appropriate, “Who is this that obscures divine plans with words of ignorance? (Job 38:2). A fuller admonition, which might have been leveled at Leibnitz, Darwin, or Bacon, follows:

Where were you when I founded the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding.

Who determined its size; do you know? Who stretched out the measuring line for it?

Into what were its pedestals sunk, and who laid the cornerstone, while the morning stars sang in chorus and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

And who shut within doors the sea, when it burst forth from the womb;

When I made the clouds its garment and thick darkness its swaddling bands?

When I set limits for it and fastened the bar of its door, and said: Thus far shall you come but no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stilled!

Have you ever in your lifetime commanded the morning and shown the dawn its place for taking hold of the ends of the earth, till the wicked are shaken from its surface? (Job 38:4-13)

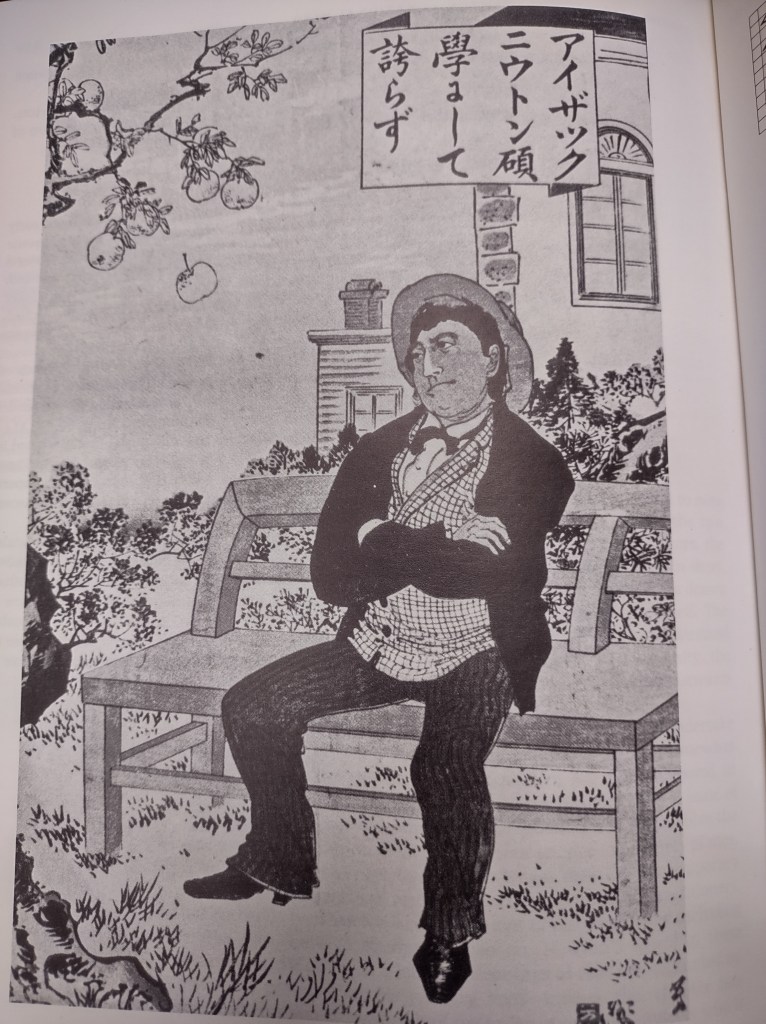

So it was, like the apple that woke Adam and Eve to an awareness and knowledge that was the undoing of their innocence, an apple fell to earth in 1666 awakening Newton to consider the laws of gravity. The former caused Man to abrogate the natural laws of God, the latter reminded Man of God’s place in the laws of the natural. So it is, the apple offers a link between the two for Newton; understanding of the natural world and a desire to realize God’s hand in it. To this, Pope lauded Newton’s accomplishments in his epitaph.

[1] Following his death in March 1727 Newton’s body lay in state in Westminster Abbey for three weeks. He is the first scientist to rest there in the Scientists’ Corner. The ashes of the famous theoretical physicist Steven Hawking rest between Newton and Charles Darwin.

[2] Gregorian versus Julian calendars. The English eschewed following a ‘Papist’ calendar. England switched in 1752.

[3] Frank E. Manuel. The Religion of Isaac Newton: The Fremantle Lectures 1973 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 30. Although Bacon’s work appeared in 1605 it stated the case clearly in the Introduction that it was for the advancement of learning, both Divine and Human, and therein the two should remain separate. Many learned men held this belief through the following century.

[4] For a more comprehensive explanation see Andrew Janiak, “The Book of Nature, The Book of Scripture,” The New Atlantis, no. 44, Winter 2015, 95–103.

[5] Manuel, 15.

[6] Irenicism promotes unity between Christian denominations and sects. Twelve editions of Observations upon the Prophesies of Daniel appeared in print between 1733 and 1922 attesting to public and scholarly interest in Newton’s theological perspectives.

[7] Newton and the Reverend Doctor Richard Bentley exchanged letters between 1692 and 1693.

[8] Fauvel, John, Raymond Flood, Michael Shortland, and Robin Wilson, eds. Let Newton be! (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 170. See also Four Letters from Sir Isaac Newton to Doctor Bentley, a bound collection of the letters from 1756, https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_four-letters-from-sir-is_newton-sir-isaac_1756/mode/2up accessed 7 November 2024.

[9] See William Whiston’s translation, https://isaacnewton.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/newton-general-scholium-in-whiston-three-essays-1713-letter-size.pdf accessed 7 November 2024. The “General Scholium” appears at the end of the third book in the Principia prior to the section titled “The System of the World – A Grand Summary.”

[10] See Andrew Motte’s translation of the “General Scholium,” to the Principia (1729), accessed 10 November 2024, https://isaacnewton.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/newton-general-scholium-1729-english-text-by-motte-letter-size.pdf