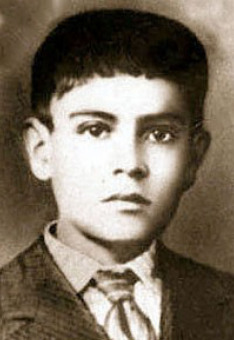

The Youngest Martyr

As he gazed through the bars of his cold cell, Jose could see the dome of night stars above. They appeared as constant and bright as the faith in his heart. They gave him hope and provided comfort during this, the greatest trial of his young life. Although his guards taunted and beat Jose, he never felt alone; he knew that the Lord had sent angels to be by his side. He could feel their wings wrapped around him and hear the encouragement they whispered during the darkest moments. For days the government soldiers starved and scourged him, reviling him for his allegiance to his Christian faith. At times they offered respite if he would only deny it and the God of his people. But he, Jose, was no apostate; he was the smallest Cristero and proud to be chosen. Like Tarcisius, whose name he bore as an affectionate appellation from the older Cristeros, he would remain true.[1] It was in this way also that St. Paul counseled Timothy his own “true child in faith” (1 Timothy 2) that he should “Let no one have contempt for your youth, but set an example for those who believe, in speech, conduct, love, faith, and purity.” (1 Timothy 4:12). Finally, on 10 February 1928, his tormentors, tired of the games they played, took Jose from his cell. They slashed the soles of his feet, so his walking would be in agony, and marched him a long distance to the place of his execution. Along the way he prayed for his captors, recited the rosary, raised his voice in praise to Our Lady of Guadalupe, and continued to proclaim his steadfastness.[2] On the outskirts of Sahuayo, the place of his birth, Jose Sanchez Del Rio died by firing squad, accepting a martyr’s death at the age of 14.

A Foundation of Faith

For generations the people of Sahuayo had placed their faith at the center of their lives. It had been that way since Francisco Coronado had arrived and the first black-robed fathers had traveled to the surrounding hills and planted their crosses there.[3] Then, when the Parroquia del Sagrado Corazon de Jesus took form and shape in the center of the small but growing town the people at last had a visible anchor and touchstone for their faith.[4] Through all that collective history the fathers had come to serve as their shepherds, guiding and protecting the people of Sahuayo from the evils of the world and from the oppressive authorities who demanded much but provided little to the farmers and laborers. For approximately 120 years, a carousel of Mexican elites, politicians, generals, and landowners, had come and gone, vying to wrest power from one another while steering the masses forward toward their personalized vision of a modernized state. In doing so, they had clung to a secular idealism that offered selective suffrage and land reforms but eschewed religion and faith. For them, the Church had become a gadfly and an obstacle, an obsolescent governor that slowed the forward movement of the modernizing impulse. The elites associated it with the lower masses, those who became disposable and had no place in the march toward a newer Mexico. So it had been, through the tempests that grew between the church and state in the early 1800s, then through the failed reconciliations and broken reforms of 1857, 1867, and 1876, and on into the early twentieth century. Powerful leaders such as the wealthy landowner José Venustiano Carranza and later the atheist Plutarco Elias Calles eventually emerged and each in turn assumed the Presidency while taking steps to strip the clergy of its agency and power.[5] This included the seizure of church property, the closing of religious schools, the prohibition of monastic vows and religious order, and the exile and execution of priests. In February 1917, during the Mexican Revolution, Carranza and his supporters had encouraged the framing of a national Constitution and its oppressive Article 130 that underscored the concept of separation of church and state by restricting the legal status of the religious body. Continuing to fear the influence of the Church among the masses, the Constitutionalists also sought to curtail its power by permitting local legislators to limit the number of clergy. Some regional leaders, such as the governor of Jalisco, acted on that initiative and forced the clergy there to register with the Ministry of the Interior. Others followed suit, and eventually by 1934 only 334 priests remained to serve 15 million people throughout Mexico.[6]

The Uprising

Through that long arc of time, the masses of the country, particularly those in the more rural areas, tired of the inconsistency and oppression of Mexico’s elite leadership. They saw in those actions nothing less than the existence of a social and cultural dissonance that marginalized them. In the Church however, the people recognized a foundation that was their bedrock. Their faith in God remained constant and any suppression was not to be borne. Those of them who spoke up earlier had won the sobriquet ‘religioneros’ a title that the leaders in the Mexican capital eventually replaced with the term ‘Cristeros’ for the central place that Christ had in the lives of the rebels. Beginning in 1926 the Cristeros organized into brigades in the western states of Jalisco, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, and Zacatecas where they fought back against their oppressors and the voices of anti-clericalism. By 1929 they had fielded approximately 50,000 rebels.[7] During their struggle, they meditated on the widow’s mite in sympathy for the poor who bore the burden of unfair taxation (Mark 12:43-44), they railed against the wealthy who failed to help the poor as did St. James (James 5: 1-8), and courageously challenged the tyrannical leaders who denied them the freedom of worship as did Daniel (Daniel 6:14-18). Until 1926 they demonstrated their resolve by engaging in open clashes with government forces. With the air echoing their battle cry, Viva Cristo Rey, they rushed into battle. Not always successful, they continued their operations for those three years, celebrating their victories but often melting away into the hills when facing overwhelming numbers. It was during one of these withdrawals that government forces captured Jose who was then serving as flag bearer for his troop. His imprisonment and torture followed. But Jose was not the only Cristeros to become a martyr. The list was extensive, amounting to 30,000 killed in defending their faith.[8] Often, the government would hang the bodies of Cristeros from telephone poles along roadways and railroads as examples to others.

During their war the Cristeros received spiritual support from Pope Pious XI who on 18 November 1926 issued the encyclical Iniquis Afflictisque “On the Persecution of the Church in Mexico.” In that document he condemned the government officials who “have ordered and are continuing up to the present hour a cruel persecution against their own brethren.”[9] Support also came from the Americans in the form of aid, food, and supplies from religious groups, and some arms from sympathetic organizations. The location of the United States also presented itself as a safe refuge for Mexicans who managed to cross the border to flee the fighting that continued with no end in sight. At long last however, the American government offered support to the Mexican government in the hopes of bringing stability to the region through a quicker end to the conflict, and with the expectation of gaining oil concessions that might resolve an expected shortage in the States.[10]

The fighting came to an end through the focused efforts of the American ambassador, Dwight Morrow, who brokered an agreement between the Cristeros and the Mexico government. Although concessions in the settlement between the two sides ultimately denied the Church any political power and influence, most of its property previously confiscated returned to its control, and it was again able to resume religious training. The Mexican government also curtailed the persecution of priests and religious leaders. From a secular perspective the powerful influence of the Christian church over the lives of the masses was broken and the rebels a mollified, but for the Cristeros it was a hard won victory. The Church was finally out from under the heel of oppression and their faith had endured another period of persecution not unlike that of the Christians living in the shadow of the Roman Empire. Regardless of the outcome, some Cristeros, angered because the government had not invited them to the cease-fire negotiations, continued their resistance. However, within a few short years it had all ended leaving the Cristeros with the understanding that they had saved the faith for their county.

Together with many others, Jose’s heroic act of faith as the youngest Cristero drew wide recognition.[11] The Catholic Church initiated the process for his canonization in 1996 recognizing him as a faithful servant. The process concluded in 2016 with his elevation to sainthood. His remains rest in the Church of Saint James the Apostle in Sahuayo, his hometown. The Cristeros’ stalwartness during time of duress, as exemplified by Saint Jose Del Rio, preserved the faith. His actions bring to mind the words of James 1:12, “Blessed is the one who perseveres under trial, because having stood the test, that person will receive the crown of life that the Lord has promised to those who love him.”

[1] Tarcisius was a twelve-year-old acolyte who died at the hands of a group of non-Christians during the persecutions of the Roman Emperor Valerian in the Third century.

[2] Our Lady of Guadalupe, also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe, appeared in four visions of Mary to a Mexican peasant named Juan Diego in 1531. The faithful consider her the “Queen of Mexico” and “Patroness of the Americas.” An attempt to destroy a painting of the Lady by an anti-cleric fanatic in 1921 failed in its purpose but encouraged the Cristeros.

[3] Francisco Vazquez de Coronado (1510-1555) explored the American southwest and areas of Mexico between 1540 and 1542.

[4] Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

[5] Venustiano Carranza was a landowner and politician who served as president 1917-1920. Plutarco Elias Calles was a politician and general who served as president 1924-1928. He founded the Institutional Revolutionary Party (IRP) and controlled the government even after his presidency until 1934.

[6] So effective was this strategy that by 1934 only 334 priests remained to serve 15 million people. See, Brian Van Hove, S.J. Baltimore’s Archbishop Michael Joseph Curley, Oklahoma’s Bishop Francis Clement Kelley and the Mexican Affair: 1934-1936, The Summer 1994 issue of “Faith & Reason.”

[7] James T. Murphy, Saints and Sinners in the Cristeros War (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2019): 89.

[8] Julia G. Young, Mexican Exodus: Emigrants, Exiles, and Refugees of the Cristero War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015): 55.

[9] Encyclical of Pope Pius XI on the Persecution of the Church in Mexico to the Venerable Brethren, the Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops, Bishops, and other Ordinaries in Peace and Communion with the Apostolic See, accessed 9 January 2024, https://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_18111926_iniquis-afflictisque.html

[10] Oil shortages in the US in the early 1920s led to a panic that domestic supplies were running low. Thus the national leadership began casting about for alternative options.

[11] Among the many who died were Father Miguel Pro, Jose Salvador Huertagutierrez a simple mechanic, Father Toribio Romo Gonzalez, and Maria de la Luz Camacho, a catechist. Since their deaths the Catholic Church has beatified or canonized each of these martyrs.